The fur trade has developed more than its fair share of mythology, either from false accounts during the era or bad guesses by modern researchers. Unfortunately, many of these colorful myths are often repeated as fact.

One such myth that I continue to hear is that the fur trading companies only hired voyageurs that could not swim.

The story usually goes something like this . . . a man who could not swim would make every effort to save his employer’s furs or trade goods. If a canoe tipped over, non-swimming voyageurs would grab for floating cargo instead of swimming for their lives.

Unfortunately, it’s nearly impossible to prove such a statement. Disproving it might be a little easier, but the best arguments are common sense and some tangential primary sources . . . not always the best way to win an historical argument!

Still, the best proof against the voyageurs-didn’t-swim story might be surviving voyageur contracts . . . not one includes any statement to the effect that the man signing could or couldn’t swim. There’s no proof in contracts or company records that non swimming men were hired more often than swimmers.

It’s even more difficult to prove that voyageurs were more easily replaced than trade goods or furs. The 1799 census listed 9,000 inhabitants in Montreal proper; surrounding areas were even more sparsely populated. Employing over 1,000 men, it doesn’t seem possible that a fur trading company like the North West Company could be quite so picky as to hire only non-swimming men.

![Plate XXIII: To Tread Water, from L’art de Nager, Demontré par Figures. Avec des Avis pour se Baigner Utilement, by Melchisedech Thévenot, 1696. [Plumb and Level]](http://www.hsp-mn.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/the_art_of_swimming__treading_water_01a1-224x300.jpg)

Plate XXIII: To Tread Water, from L’art de Nager, Demontré par Figures. Avec des Avis pour se Baigner Utilement, by Melchisedech Thévenot, 1696. [Plumb and Level]

Another argument in favor of non swimming voyageurs was that “nobody swam back then.” Not exactly true since swimming was becoming more popular, especially among the literate elite.

Books on swimming and lifesaving had begun appearing in the mid 1500s. In 1696, French author Melchisédech Thévenot wrote “The Art of Swimming.” Translated into English, it became the standard reference for many years to come. Benjamin Franklin taught himself to swim with this book, and in March of 1780 the London Chronicle printed a letter he wrote to a friend on how to improve his swimming.

Still, finding men among the lower classes, such as those that typically produced voyageurs, that didn’t swim would be a pretty easy task. Hardly something a powerful company in need of employees would spend a lot of time thinking about.

The best argument against the story might simply be the human instinct for self-preservation. If a man is suddenly dumped into water, most likely he’ll flail his arms, kick his legs and thrash his way towards shore. He might even try to grab on to something floating by, whether it’s a broken paddle, company cargo or a fellow voyageur.

Floundering in the water, I’m pretty sure my first thought wouldn’t be saving my employer’s property, regardless of whether I was hired for my swimming skills or not!

When I’ve asked for the source of this statement, most re-enactors who tell it as part of their interpretation, usually mention the staff at such-and-such fur trade site or a book they can never remember the title of as their source.

So, where did this story come from? If we really don’t know where this story came from, and can’t prove it (or disprove it) with any degree of validity, maybe it’s time to stop telling it as truth?

For a related discussion about whether or not Englishmen in other North American colonies swam, see the article Colonial Americans in the Swim by Harold B. Gill Jr. at http://www.history.org/Foundation/journal/Winter01-02/Swim.cfm

Nicely done, Jacki!

(James Birnie descendant) In my research for current York Factory Express book, I have found voyageurs who drowned in rapids on the Saskatchewan River, and some who swam ashore on the Athabasca (to the jeers of his friends). So both arguments seem good. Good to hear from you.

I came across another early reference to swimming – not in a fur trade context, but I thought folks might be amused.

Giacomo Castelvetro (1546-1616) wrote in 1614 of children in Italy learning to swim while using dried pumpkins as PFDs.

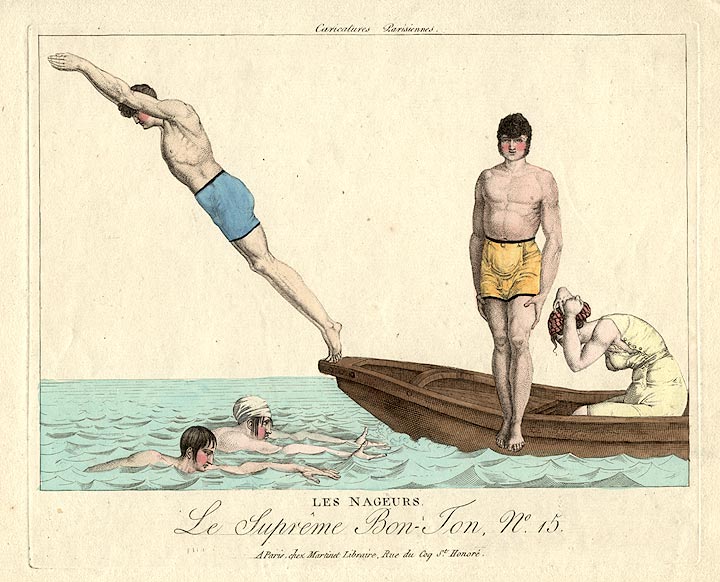

I have spent quite a bit of time researching swimwear during the mid-19th century and I’m quite intrigued by the Bon-ton plate – do you know the date of it?

Thank you!

Thanks, Kelly for your question . . . the information I have on the image is “Anonymous: Les Nageurs (The Swimmers), from the series Le Supreme Bon Ton, No. 15, Martinet, Paris, c. 1810-1815.” Although I have no idea where the original image is, I hope this little bit of information helps with your research.