Once upon a time, veteran La Compagnie member Tom Brennan set down his thoughts about his “personal adventure of interpretation.” The idea was that it would form the basis of a entire Journal issue on interpretation. That issue never happened. Years passed. Tom got sick and died. More years passed. Now, after an embarrassingly long delay, here are his “ramblings.” Still relevant, still inspiring. We miss you, Tom.

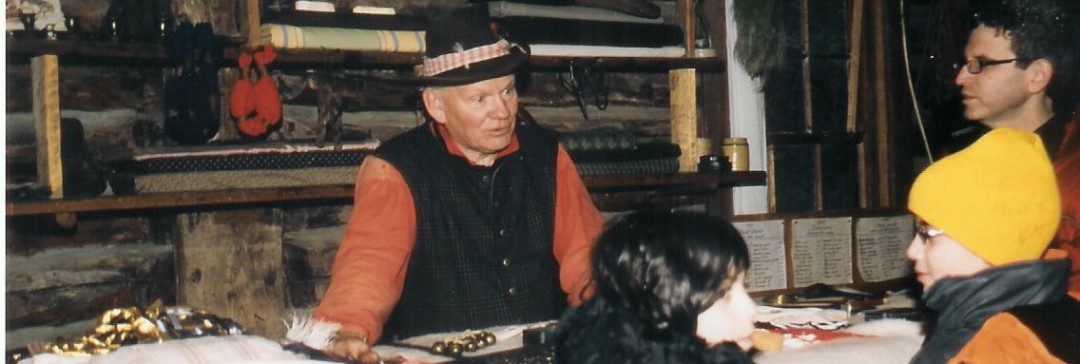

Spring Thaw training, 2008. Photo courtesy of Ron Engh

It is hard to recall when this adventure began for me. In one sense, it began almost half a century ago when I discovered the canoe country of northern Minnesota. I tried to connect what I found there with accounts in the old books and journals of the fur trade era.

When first I was invited into this new way of learning of history, I was transported back in time, to a degree, which allowed me to experience the events with new insight. It is one thing to read about the voyageurs falling into a sound sleep on rocks and sticks because of sheer exhaustion —and another thing to do it myself. Developing such insights allowed my sharing of history to expand and become more alive.

Where I have always struggled is in the question of what is it that we do when we interpret a different era to others. Having a love of teaching is central, but interpretation is not quite teaching for me. Having a love of acting gives life to some characters, but interpretation does not quite seem to be just acting. Then there is the pure joy of setting aside so many of the trappings of modernity and living simply, but interpretation is more than simple escapism.

Let me try to describe what I have discovered along the way, the basic principles of interpretation that I have developed over the years. These thoughts are truly ramblings. Others may have more refined and better presentations than mine.

The old voyageur and a young scout. Photo courtesy of La Compagnie archives

Interpretation is an invitation to experience history personally. The visitor is allowed to glimpse the past in an interactive manner. It begins with the eyes and a visual image of the past. Like a living diorama in a museum, the visitor approaching our camp is presented with a three-dimensional picture of what life might have looked. For that reason, it is important to me that what is seen is as accurate to the period as we can understand it—almost as if visitors accidentally stepped back into another time.

Our interpretation starts with what we wear, what we are doing and how we interact with one another. It therefore is important to talk to experienced interpreters regarding the basics of clothing. Ask about borrowing clothing and seek out resources that will keep you from making incorrect choices as you begin.

Interpretation is an invitation to interact with someone who “lives” in the past. We have little idea why people come to our event or what they expect, but as we invite them into conversation we aim to tweak an interest that lies below the surface. Often it is necessary to begin with a brief introduction of basic information so the person does not feel totally out of touch in this unusual environment in which he or she finds themselves.

It works best for me to follow the initial “setting the scene” statement with questions that invite them to participate at their level. “What do you think you would want from the only store bringing goods from the outside world?” “Would you like to hold the musket?”

The musket will certainly lead to a discussion of hunting techniques and even cultural interactions.

Fur trader Tom Brennan, The Landing, 2009. Photo courtesy Nancy Powell

Interpretation is an invitation to others to have fun with us. Most of us do not get paid for re-enacting so our reward is the fun that comes from living history ourselves. For the most part it adds to the joy of what we are doing if we continue after the public leaves. We see little need to haul out the modern gear; we enjoy the flicker of the candle lantern.

Sharing stories as we stretch out on a blanket before the fire is part of the reward of doing an event, as is the pleasure of watching visitors absorb history and not even recognize it as that dreaded subject from school. One fourth grader made my day. He wrote—on instruction from his teacher obviously—to thank me for a class presentation and ended by saying the best part was “we got out of social studies.” Visitors generally seem to enjoy “suspending the obvious” and want to live with us for awhile in a different time.

I count the number of children and adults who have shown new interest in history because of my efforts as a real plus in my life. I trust it will be the same for all who continue to walk this journey.

Next : So how do we do this thing?

I was a member of La Compagnie many years ago. I have to agree with what Tom has to say. I will always remember my first canoe trip in 1983. Six days in a canoe on the Mississippi River. I am still a reenactor, just moved on to the 1860’s and Civil War.

Tom was a great interpreter on many levels, and with many interests, a true hands on guy! I will never forget Tom out ran me (and everybody) on the way down the entire Grand Portage trail, after a week of canoeing and portaging. Strength of body, mind, spirit. Thanks for sharing this.